“One day, a soldier called and said, ‘Chaplain, I want to talk — it’s hard for me.’ I asked, ‘Can I call you back later?’ I tried several times afterward, but he never answered. Later, I learned he had taken his own life.”

This was one of the sobering moments for Ukrainian chaplain Maxym Abramov. For soldiers in training or active combat, the weight of war is crushing, and many desperately seek connection — something that bridges them to a reality higher than the chaos around them. But with the demand far outpacing the number of chaplains, stories like this happen. For Maxym, it was a stark reminder of the urgency of his calling: “I will never again postpone phone calls, meetings, or anything else," he says. "This is the reality we live in. And if I didn't help, then part of that responsibility is on me."

The chaplain’s day begins with morning formation, followed by a meeting with the deputy commander. If the chief of chaplaincy assigns him a task, he sets out to visit various units — battalions, individual companies, and platoons. His goal is to be present with them, even if only for an hour or so at each location. On some days, he interacts with around 150 people — sometimes even up to 300.

Photo provided by Maxym Abramov

The scale of his outreach is driven by necessity. Among those he meets are soldiers who are wounded, missing, or require burial arrangements for the fallen. This constant demand shapes his schedule. If he isn't assigned a specific task, he actively seeks out those who need him and fulfills those responsibilities. But it wasn’t always that way.

Life in Occupation: Where is God in Suffering?

Maxym Abramov didn’t always envision himself as a chaplain. In 2014, he was a 16-year-old schoolboy preparing for graduation when Russia first struck his hometown of Slovyansk. On April 12, he was driving home from his grandmother's house in the city center, where riots had begun. His mother turned on the TV, and they saw their city being broadcast on Ukraine's central channels. Police were already present, and his father remarked, almost prophetically, "There will be war." Shortly after, the three-month occupation began.

Maxym Abramov vividly remembers that time: “First, there’s a certain shock — you’re just stunned by everything that’s happening. Second, you start to accept the fact that you can’t leave. There’s nowhere to go, and you’re stuck. Third, you begin to realize that your views are sharply different from those around you — from the people [Russian occupants – editor’s note] who are making all the moves, controlling everything. And fourth — that’s when I lost hope. I stopped believing that anyone would come to liberate us or that things would change.”

The experience of living for three months under occupation, coupled with the uncertainty of the future, shattered Maxym's perception of life, plunging him into deep depression. Eventually, it drove him to the brink of suicide. That was when he found Christ. “My material world simply collapsed like a house of cards,” he recalls. “And I realized that in Jesus Christ, there isn’t just hope — He is the very meaning of life itself.”

Armed militiamen occupying the council building on 14 April, 2014 (photo courtesy of Yevgen Nasadyuk)

Maxym began to dig deeper into Scripture, even as war raged in eastern Ukraine, just centimeters away on the map from his hometown. Questions about God's presence in times of suffering weighed heavily on him. Seeking guidance, he turned to his church. He approached the leadership with a pressing concern: how could the church respond to the crisis and the possibility of further escalation? Their response, however, was that their current efforts in rehabilitation ministry and humanitarian aid were sufficient — and that his questions were leading young men to lose their faith. Left without support, Maxym was forced to wrestle with his doubts alone. He turned to apologetics, theology, and other fields to strengthen his faith and understanding, eventually enrolling in a Christian seminary.

“I do not understand myself outside the context of war. For me, everything that is happening now in Donbas is inseparable from my understanding of myself. Even my theology was formed precisely within the context of this conflict,” he explains.

Becoming a Soldier: “for Greeks he Became Greek”

By 2017, as the war dragged into its third year, bringing increasing suffering to both civilians and defenders, the need for a steadfast source of hope had become undeniable. During a visit to a rehabilitation center, Maxym met a soldier who had survived the brutal battle at Donetsk Airport. The soldier spoke of a chaplain who had stood beside them in the thick of the fighting, offering comfort and support amid the chaos. That story deeply impacted Maxym and helped clarify his calling. He decided to pursue military chaplaincy. “I want people to come back,” he said. “Sons — to parents, husbands to wives, fathers to children.”

However, the war still felt distant to Maxym, and he experienced a sense of disconnection from the soldier’s stories. To truly understand and eventually be able to help those like him, Maxym decided to join the army himself. “To truly understand the military, I had to become one myself. It's almost biblical — I would call it an axiom. Like it says in the Bible: to the pagans, as a pagan (but without crossing the line); to the Jews, as a Jew; to the fishermen, as a fisherman. And so, to the military, as a military man.”

This decision cost Maxym his first church in Slovyansk. When he expressed his desire to gain military experience, the church cast him out. It was another painful blow. Ironically, after the full-scale invasion, Maxym returned to that same place — this time with firsthand experience to share. The new church leaders welcomed him warmly and invited him to teach and minister to others.

During training and military service, the character of each man was tested under immense pressure, as they were transformed from civilians into resilient, disciplined, and skilled defenders. Yet not everyone who trained was able to endure the burden. One young man in Maxym's circle tragically took his own life, shooting himself in the head.

Volunteers listen to an instructor during basic training, Ukraine January 9, 2024. Photo courtesy of Viacheslav Ratynskyi via Reuters

Maxym later joined the National Guard and signed a contract to serve in the Donbas Battalion. He was eventually selected for sergeant training. His first direct experience of war came after the full-scale invasion in 2022. The intensity of battle — storming and defending positions, living under strict military discipline, and being fully immersed in the atmosphere of war — shaped his understanding of the Bible and what it means to live out faith on the front lines. In this view, Jesus is the Supreme Commander (Sabaoth), who leads us in spiritual battles and gives orders that we are called to obey. Just as the army functions as a community, so too does the Church.

“When I became a soldier, I began to understand the Bible in a profoundly new way — through the lens of a warrior. When I read that I am a soldier of Christ, I no longer imagine some kind of plastic authority or a paper-thin breastplate. No — I now understand that a soldier is someone who truly fights. The army taught me that faith is not some fragile or decorative theology,” he explains.

Surviving the Deadly Attack

Together with his fellow soldiers, Maxym took part in numerous battles, fighting to drive the Russian forces from Ukrainian soil. In one of those fierce engagements, on May 5th, 2022, he came perilously close to losing his life. He recalls: “By 2022, the war had entered its third month. We were tasked with defending a stretch of the front line under heavy assault. The artillery barrage was relentless — it lasted more than 12 hours. We did everything we could to hold our position.”

Then, in one devastating moment, Maxym was wounded. “Just two meters behind me, a fellow soldier — his call sign was “Banker” — was sitting diagonally across. A piece of shrapnel struck him in the neck. He died instantly. If he hadn’t been there, that shard would’ve gone straight through me. Instead, I was hit with smaller fragments. A chunk of flesh was torn from my leg, and one piece grazed my back and side. I watched the blood pour from his mouth. I saw the exact moment life left his body.”

The pain that followed Maxym was unbearable. He describes it as sharp, burning, tearing, and crushing — all at once. He couldn’t move his arm, yet was ordered to make his way to the evacuation point, about one kilometer away. He ran, fell, got back up, and ran again — ducking under fire, hitting the ground, then pushing forward once more, as the enemy deployed cluster munitions in the forest.

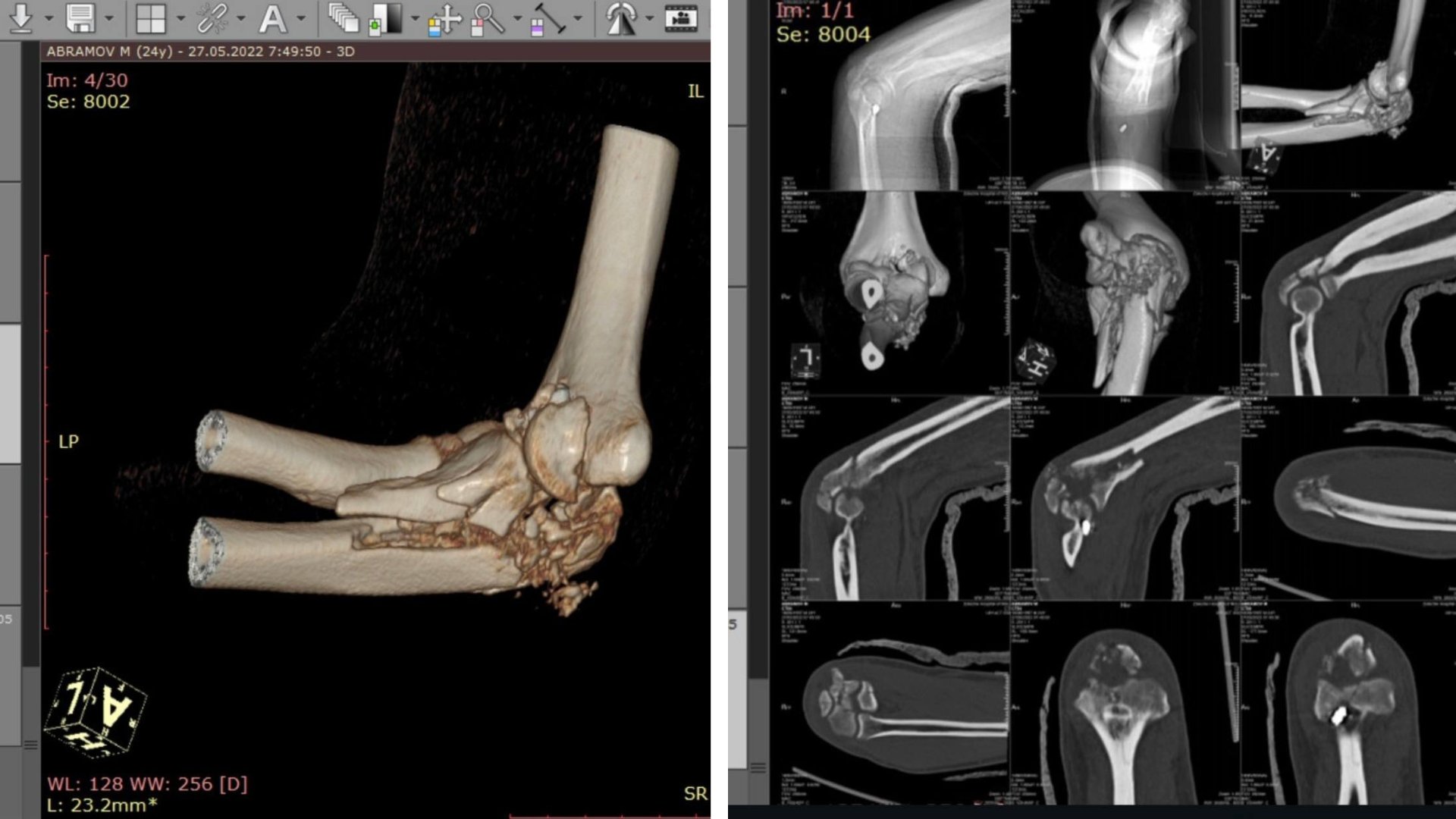

“They brought me to a hospital in Bakhmut,” he recalls. “The doctors examined my arm and said things looked grim. The damage was so severe, I still don’t know how God saved it. But He did.”

Scan of Maxym Abramov's injured arm

He was later transferred to Germany, where he underwent a long and difficult rehabilitation. At that time Maxym understood something deeper: if he hadn’t been wounded, he wouldn’t carry the kind of “badge” he does today. As a full-time chaplain in the brigade, he no longer comes to the soldiers as an outsider with good intentions — he comes as one of them. He can walk in and say, “Glory to Jesus Christ,” and they listen. “I’ve earned the right to speak to them about hope,” he says. “But more often, my job is simply to listen.”

In December 2024, nearly a decade after the beginning of Russia’s war against Ukraine — including the conflicts in Donbas and the annexation of Crimea — Maxym became a certified military chaplain. He now serves as a chaplain in the National Army and holds the rank of brigadier in the civil service. He also partners with the Christian Rescue Service ministry.

The Challenge of Helping Veterans

It is estimated that, in the aftermath of the war, Ukraine will have up to five-six million veterans. Their needs will be diverse — from physical rehabilitation to psychological support, from reintegration into society to reconciling with their families, and much more. These veterans carry with them the weight of war, with some having processed their trauma, while for others, the scars are still fresh. Defenders will have questions and needs that the Church, or its representatives, must be prepared to navigate with compassion and understanding.

Maxym Abramov shares: “But I must say this: many churches are not ready to receive soldiers. Even if they try, they often won’t know what to say — because the questions that come from war are different. A soldier might sit in the pew and think, ‘Pastor, with all due respect… what can you possibly tell me if you’ve never been there?’ A polite man may not say it out loud, but deep inside, a quiet rebellion stirs: I don’t want to be here. You’re trying to teach me things you don’t truly understand.”

One of the things Maxym believes should change is the approach of sharing the Gospel. The old models of ministry, the ones that worked in the ’90s and 2000s, when churches were filled with prison outreach programs, may not work here. Back then, people came from prison with a clear sense of guilt: they had stolen, harmed, broken laws. The message of Christ as the one who forgives, who stands before the Father as our advocate, fit naturally. It made sense because guilt was understood — and grace became a lifeline.

Maxym continues: “But the soldier who returns from war — wounded in body, splintered in soul — does not carry guilt in the same way. If we try to place the same model of evangelism on them, it will fall flat. What a soldier needs is not condemnation, but understanding. Not a sermon about sin, but a word of healing. Inside, they carry devastation. They don’t need to be told they’re broken, they already know it. What they long for is to be made whole. So instead of preaching guilt, we must offer restoration. Instead of pressing their wounds, we must offer balm. Only then can we begin to speak of Christ, the one who does not condemn, but heals. The one who brings peace to the war within.”

Practical Response to the Challenge

An emblem of a gray rhino with a white horn marks the face of a new initiative launched by Maxym Abramov, his friends, and fellow ministers — the “Covenity Veteran Community.” Designed as a response to the needs of Ukraine’s war veterans, the initiative offers more than support — it offers belonging.

The mission of Covenity is threefold: tactical, operational, and strategic. Its guiding code defines key relationships — between the individual and God, others, and the state — forming a clear foundation. Legally, the community operates within the framework of Ukrainian public organizations and fully complies with national law.

Covenity is an interdenominational community that welcomes Orthodox, Roman, and Greek Catholics, and Protestants of all backgrounds. Each tradition is honored, but members are united in Christ and bound by brotherhood. “We are the shell-shocked — but I mean that in the best sense. We've endured the trials of this earthly battlefield, and now we know how to support one another. We emerge as wounded healers, ready to serve those around us. And thankfully, there are already quite a few of us who truly understand the context,” adds Maxym.

Logo of Covenity and photo provided by Maxym Abramov

Why rhino? The rhinoceros is the only animal that cannot step backward — it simply isn't built for retreat. With a massive body and the ability to charge at over 30 kilometers per hour, its strength is obvious. But more than power, it carries symbolism. Its skin is among the thickest in nature, yet beneath it lies a soft heart — a rare balance of toughness and vulnerability. Most striking, however, is its horn. Made of tiny, fragile fibers, each one weak on its own, yet when bound together, they form one of the strongest natural materials on earth. “That’s what we are. Each of us, on our own, might feel small or breakable. But together — we are like the horn of the rhino: strong beyond measure. That is the foundation we build on. That is the spirit of the rhino — the spirit of unity and unstoppable strength,” Maxym explains.

The challenge remains to expand the number of chaplains to meet the needs of 5-6 million veterans, establish more partnerships with organizations both within Ukraine and abroad, and secure the necessary financial resources to make it all possible. Partnering with Christian Rescue Service, this vision is starting to come to life.

The principle of truly understanding the people you serve is a cornerstone for Maxym Abramov and other military chaplains in their daily work. As Russia's war against Ukraine continues, the demand for spiritual support — for defenders both on the front lines and as they transition back into civilian life — becomes ever more critical. It is not only a means of sustaining morale during battle but also a step toward building a healthy, resilient Ukrainian society for the future.

Maxym's journey from surviving occupation and finding Christ, to fighting in active combat, and finally embracing the challenging ministry of serving fellow defenders, reflects the kind of leadership desperately needed. Even when the war ends, its consequences will linger for decades, especially in the hearts of those who fought. And for that, the need for the hope of Christ, understanding, and spiritual restoration will be greater than ever.